AI and the Math Olympiad

I recently took a look at the AlphaGeometry paper published in 2024. There was a lot of hype around it when it came out. People feared that AI has become too capable – if it can solve olympiad level maths, it probably can do almost anything. And what is the point of studying maths if AI can do it all?

While the results look impressive, reading the paper does help demystify the algorithm and make it appear less intelligent. It is undeniably a massive feat to solve olympiad math with AI, but the applicability to other domains, even within maths, is not so clear.

Synthetic Data Generation

A major difficulty in using AI to solve geometry problems is the lack of training data. It requires lots of manual effort to translate human proofs into machine intelligent language.

Instead of relying on human data, AlphaGeometry proposed a way to generate synthetic geometry data. The data contains geometry theorems and the corresponding proofs.

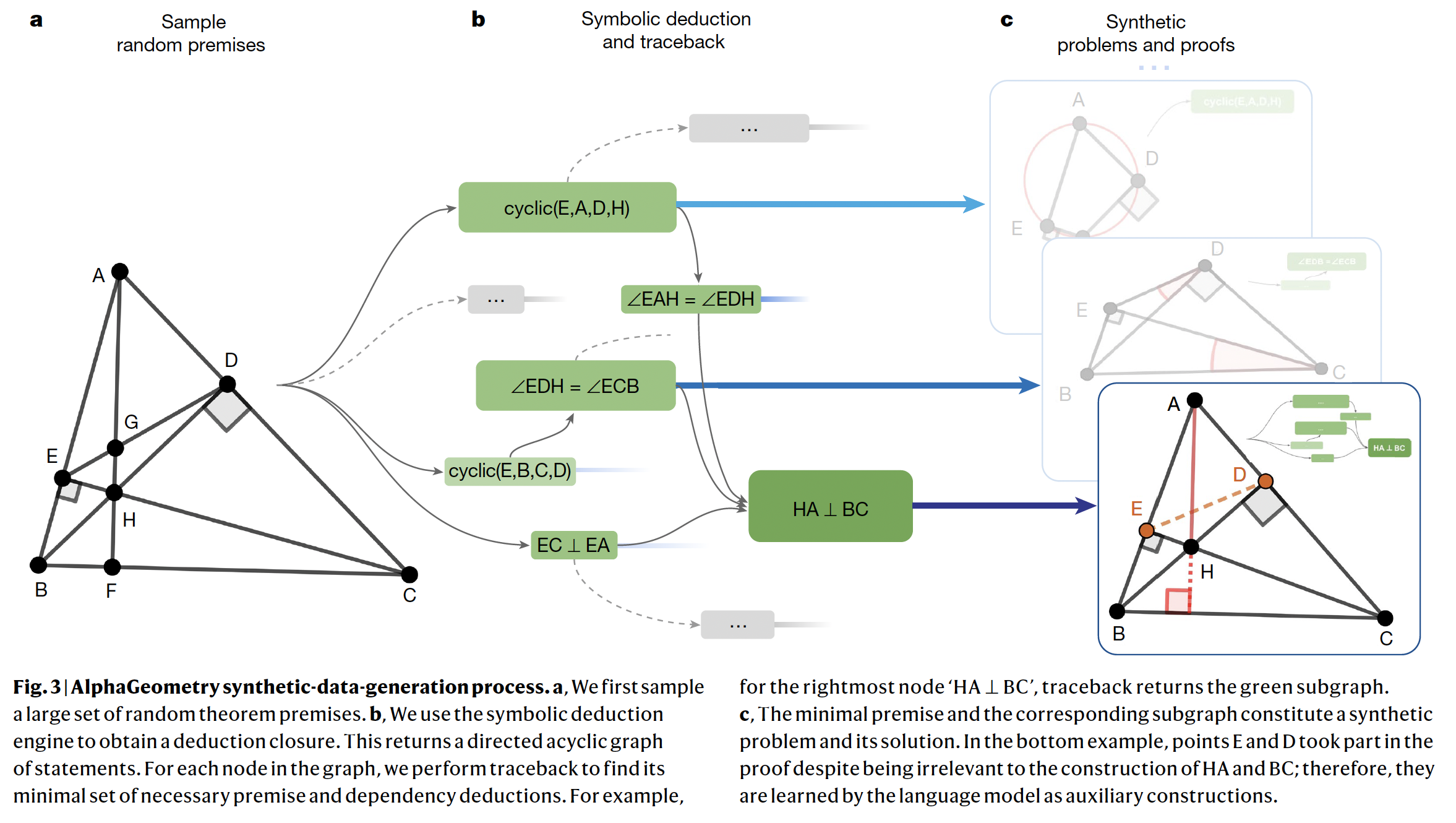

Synthetic Data Generation Pipeline (Image Source: Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations)

The generation process is summarized very clearly in Fig.3 in the paper. I also briefly describe below:

Constructing Random Premises

The first step is to construct premises. Premises are a set of given conditions. For example, the starting geometry in Figure 3 contains many premises. There are several triangles and perpendicular segments. Note that these are only conditions – we still don’t know what needs to be proved here.

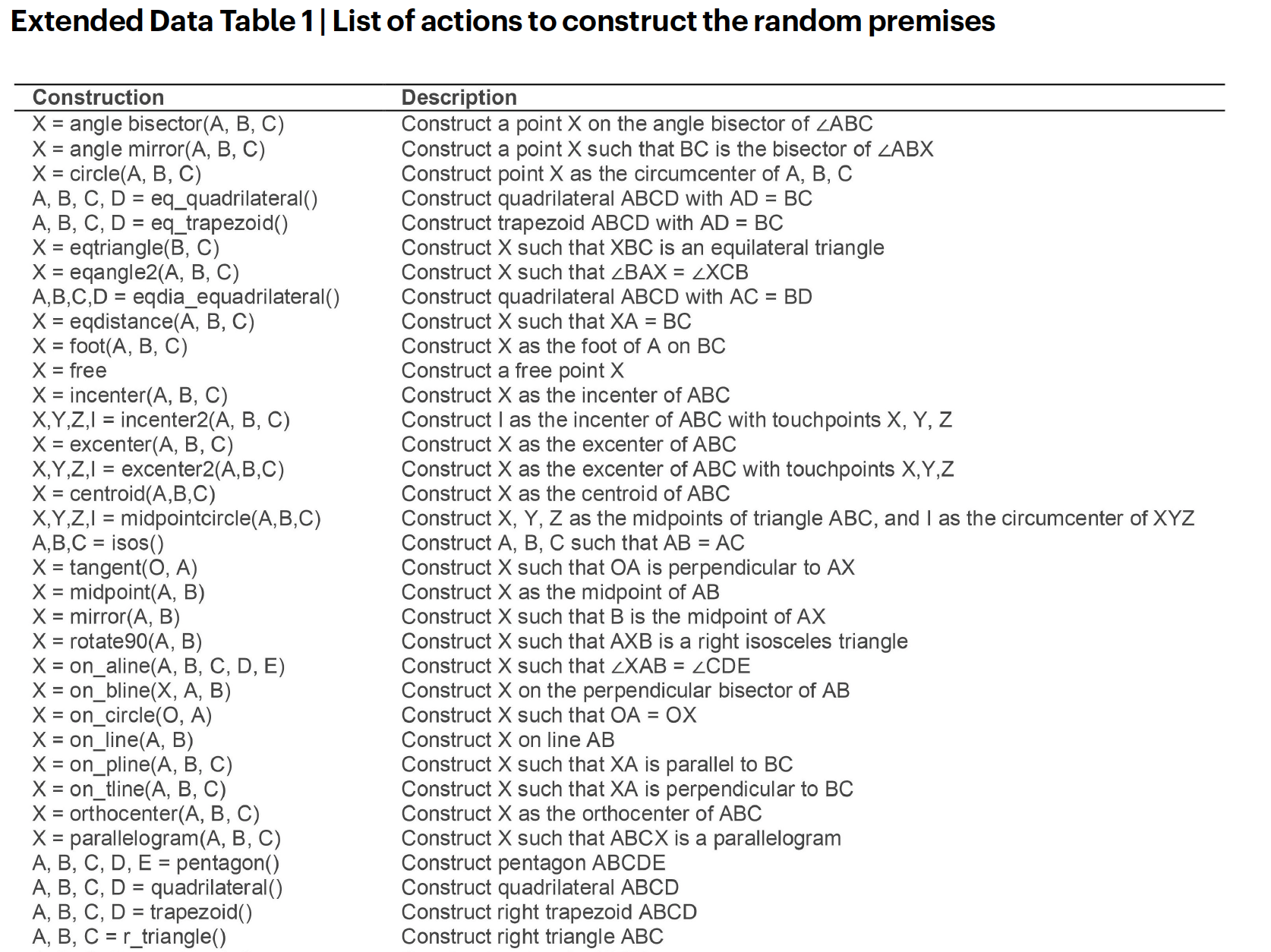

The premises are constructed from a list of domain specific phrases proposed by the paper (see examples in the Figure below). Most Olympiad geometry problems can be represented by some sort of combination of these phrases. The paper uniformly sample from the list and combine them to form premises.

A Non-Exclusive List of Domain Specific Language to Construct Geometry Premises (Image Source: Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations)

Deduction and Traceback

The next step is to derive statements from the premises. They use a deduction engine called DD+AR for this task. I am not very familiar with how the method works, but there is no machine learning involved in the process.

For each statement derived, they then trace back the deduction process and look for the minimum set of premises needed to arrive at the statement. The premises and the statement together give a theorem that can be proved, and the deductive process constitutes the proof.

Finding Auxiliary Constructions

A key innovation in this paper is auxiliary construction. They define auxiliary construction as any statement that is needed in the proof but is irrelevant to the conclusion. In the example they give in Figure 3, the conclusion is HA perpendicular to BC. Points E and D took part in the proof but are irrelevant to the conclusion. So they are considered as auxiliary constructions and will be learned by a language model.

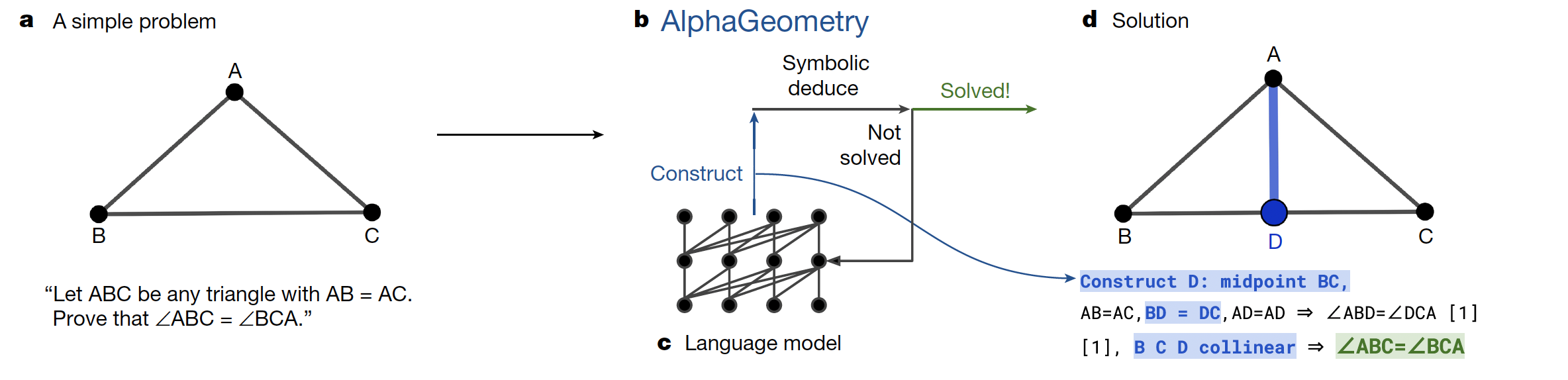

Using Language Model to Generate Auxiliary Constructions

Generating auxiliary constructions is the creative part when proving a geometry theorem. AlphaGeometry proposed to use a language model for this task. The synthetic data is processed into text strings in the form of “<premise><conclusion><proof>”, and the language model is trained to generate proof conditioned on the premise and the conclusion.

Note that auxiliary constructions are part of the premises during synthetic data generation. We simply identify them through tracebacks. During training, we need to move them from the premises and into the proof, so that the language model can learn to generate them.

Proof Search Algorithm

AlphaGeometry combines language model and the deduction engine to do proof search. The language model suggests an auxiliary construction, and the engine uses it as input to perform deduction. If the conclusion is reached, then problem solved. Otherwise, the language model will suggest a new auxiliary construction, and the loop repeats. Each construction is conditioned on the problem statement plus all the past constructions.

They use beam search to keep the top K constructions suggested by the language model, and explore these constructions in parallel.

The language model is pre-trained on all synthetic proofs and then fine-tuned on proofs that contain auxiliary constructions. The paper reports that pre-training is important as it helps the model learn the details of the symbolic deduction engine. The purpose of fine-tuning is for the model to be better at the assigned task during proof search, i.e. generating auxiliary constructions.

Proof Search Algorithm Combining Language Model and Symbolic Deduction Engine (Image Source: Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations)

Evaluation

Dataset

The paper curated a set of 30 geometry problems from the Olympiad since 2000. These problems are exclusively classical Euclidean geometry problems. It is interesting to note that many geometry problems cannot make the cut, for example, geometric inequality and combinatorial geometry, as they cannot be represented by the domain specific language.

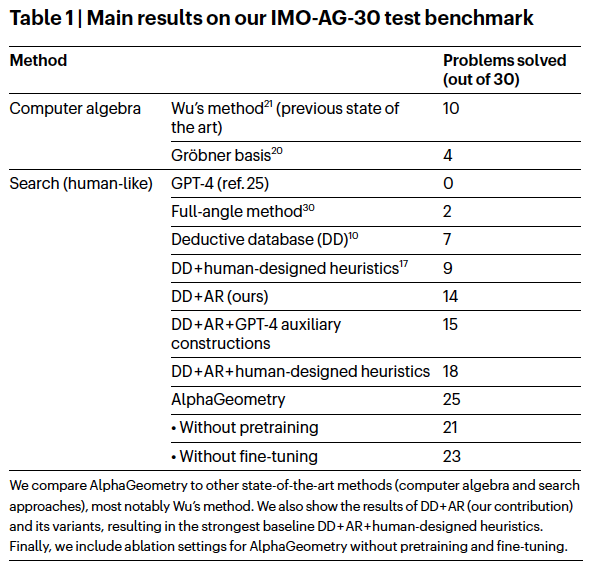

Baselines

The paper reports two types of baselines: computer algebra methods and search methods (which usually involve symbolic engine + human heuristics or large language models). It is funny that they mentioned that GPT-4 can solve 0 out of the 30 problems.

Results

The paper provides main proving results in Table 1. It is interesting that although GPT-4 by itself cannot solve anything, when combined with DD+AR it can solve 15 out of 30 questions. That is impressive considering that it is not specifically fine-tuned for solving Geometry problems. But then again, the massive training set probably already contains some of the solutions.

Evaluation Results Using AlphaGeometry and Various Baselines (Image Source: Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations)

Applicability to Other Domains

As you may realize, the algorithm itself is very specific to a certain type of geometry problems. The general framework is probably extendable to other domains. I quote from the appendix that it requires four ingredients:

- An implementation of the domain’s objects and definitions.

- A random premise sampler.

- The symbolic engines that operate within the implementation.

- A traceback procedure for the symbolic engine.

However, each part requires non-trivial engineering for it to work properly. Creating an algorithm for a completely new domain would be like inventing something new all over again. The target domain also needs to satisfy certain criteria. For example, I would imagine that the framework can work well for a domain that demands a similar level or notion of creativity. The type of creativity involved in writing a fiction novel is probably very different from that required for proving theorems.

References

[1] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06747-5

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNK4nfgNQpM